Zines: Topics of Sci-Fi and Punk Rock

The integration of zines into popular culture can be dated back to the 1930's when The Comet first debuted. Early on, the zine was common to sci-fi topics and fanfic, especially into the 40's and in the wake of WWII. However, as the popular publications grew into the 70's and 80's, punk rock discourse became a prevalent publisher of zines. It was a means to self-publish and circulate information, ideas, taboo topics, and reform. Zines on punk culture, music, and focusing on punk masculinity were prevalent within the early stages of punk rock culture, but were then combated with zines like Riot Grrrl in the 90's that specialized in addressing ideals of femininity and responding to the prior male dominated punk world of the 80's. Riot Grrrl became a stable of feminist zines, and attributed raw and taboo materials as their content.

Digitization of zines and going backwards

In the 70's, new technological innovations were contributing to the digitization of many industries, including mass producing zines. The move was mimeographs, as was used prior, to printers with the ability to print large quantities of product at a lower cost were beneficial for the low cost of zines, both in circulation and being made. The ability to print more zines than before aided in the distribution of zines, where culture statements, movements, fanzines, and radical ideas were more readily available.

As the integration of the internet became a prevalent contributor to culture at large, so did the ability to create zines digitally and sell them online, self-publish online, and create to print out physical copies. Many zines are still made on digital platforms, but fewer and fewer are using digital means to create their publications. While many zines use their own webpage or shop to promote and/or sell their zines, there is a revert back to physical publications over digitized ones. Why?

Zines and gaming culture

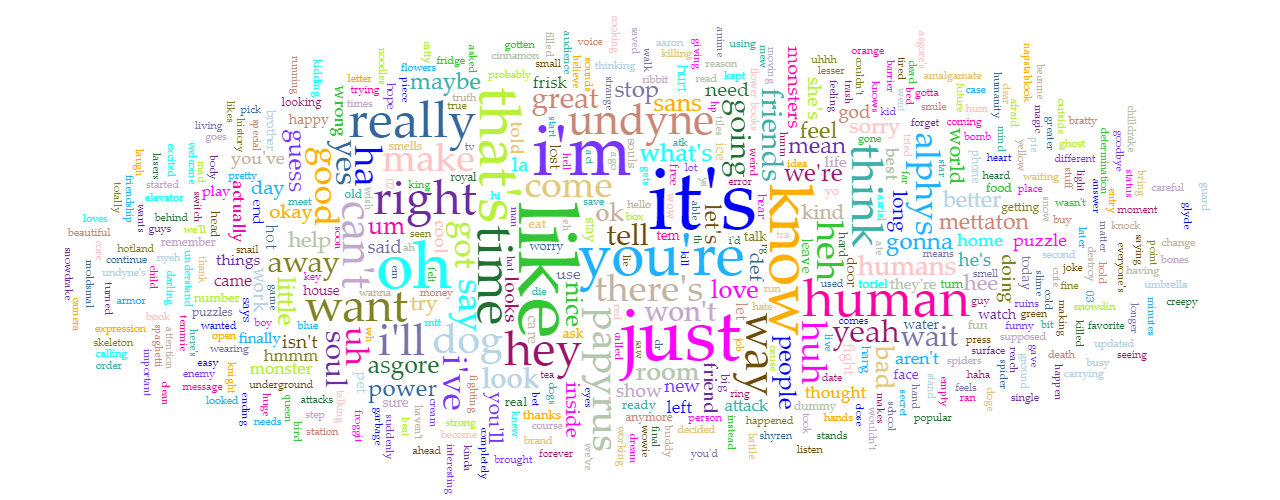

Gaming culture has been an influence on zine creation as a topic of interest for publication. As a community, gaming contributes to both fan specific publications as well as technical or more socio-political zines. The Indie G Zine is a zine focused on, specifically, indie gaming, while other zines focus on other genres, specific games, topics in games, and conversations within the community, such as dungeon crawlers in the zine Crawljammer. Game specific zines focus on, typically, cult-status or story-based games, such as Earthbound in the zine Psychokinetic.

Topics surrounding gaming culture and the community within are also addressed in zine publications. Rise of the Videogame Zinesters focuses on a collection of essays-made-zines on gaming, while zines that focus on a specific group of gaming individuals such as Letters from Incarcerated Gamers and Why FIGHT! (women in games and comics) are widely circulated.

While specifics of gaming culture are often rooted within zine publications on the topic, fanzines do not stop at Doctor Who and sci-fi fantasies. Rather, video game spoofs, fanfiction, and interpretations of games are also covered and published as zines. Due to the self-publishing context of the zine, individuals can create and publish on topics of their interest without condemning constrictions and feedback that may impede on other modes of publication.

The importance of zines within gaming culture does not stop at the contribution to the community and the continuity of representation of gaming culture as a whole, but promotes and fuels the attribution of stories to the gaming sphere. Zines create a platform where individuals can create and circulate not only topics of academic or socio-political platforms and discussion, but also interpreting stories, creating spoofs and fanfiction (as I mention prior), and contributing to the storytelling element of gaming culture. As the story is a major component of gaming genres such as RPGs and indie games, the ability to add to this community and base line of stories creates a larger conversation of what is being told in gaming culture, what are the games doing in terms of interaction with the player, and the implications of using story as the primary driving component in gaming.

Against the norm

Zines have always been used either to promote ideas shared by a small group, to contribute a sense of community, or relate radical and taboo ideas. Zines were made as a way to self-publish, either cheaply or completely free, and without the constraints of typical publications such as magazines and periodicals. No one was constricting what could be done, created, published on this platform.

However, as the world of digitization has come and, with it, brought new ways to promote and sell zine publications, there is still this animosity towards the digital version over the physical zine. This is telling to the point of the zine, as a means to go against the status quo, and circulate self-published work with information pertaining to any particular topic. Often they were an act of resistance, contributing to a conversation that was not being had or being made aware of, but should be. The physicality of the zines was important to their circulation, and the prospects of drawing on an actual piece of paper to create the zine was, and still is today, used as a common mode of publication.

The aversion to complete digitization of the zine, and the revert back to the physical, speaks on the modes in which, culturally, and as humans, we value things we can touch and feel. Something on a digital platform has no weight to us: we can not feel it, hold it, flip through the pages, smell them, and appreciate the publication in front of us. Instead, zines become flattened to digital realms and lose a bit of their original purpose.

Why are zine publications reverting back to physical copies in other contexts? Why would this be an important attribute of the zine making and reading community? And can we, as humans, value something digital like we do the physical?